Oldenburger

Münsterland (aka Niederstift Münster or Südoldenburg)

Description:

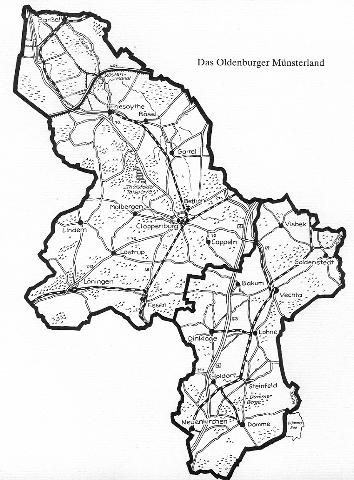

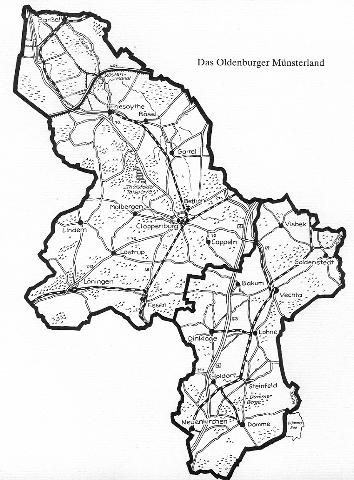

The name of this region can instantly

create confusion as to its geographic location. Is it a part of the Münsterland

or a part of the old Grand Duchy of Oldenburg? Its borders are best described

along present diocesan lines which include the Deaconates of Cloppenburg

(founded 1628), Vechta (1628), Löningen (Cloppenburg until 1954),

Friesoyte (Cloppenburg until 1927) and Damme (Vechta until 1927). It becomes

clear then that Cloppenburg and Vechta were the basic "religious" territories

which make up this region. The dioceses of Hildesheim and Osnabrück

surround the region.

Until the post WWII era, when

refugees from the east came to settle here, this was a veritable diaspora

of Catholicism in northern Germany. It all goes back a long way.

History:

History:

Since religion has set the borders

and cultural background, it is also religion which for the most part makes

up its history. All this goes back to the powerful Count-Bishops who ruled

both Münster and Osnabrück as both lay and spiritual fiefs. In

1532 Franz von Waldeck started to change his domains to the Lutheran faith.

The Cathedral Chapters of both cities resisted the loss of their powerbase

but the Hochstift Osnabrück to which the area belonged began to wane

and Protestantism had arrived. When the Count Electors of Cologne and Bishops

of Münster and a few other places started to attempt to bring the

church back to Catholicism, they found little enthusiasm to go back. The

priests had by now married their concubines and the concept of inheriting

and passing the goods of the church on to the family had made strong inroads.

The bishops did not like this idea at all but did not quite know what to

do with the wives of the priests. Basically there were only three unmarried

and Catholic priests in the area of discussion. Other promised to change

to keep their jobs but as soon as the administrators left they resumed

their old ways. In order to facilitate some local control the Count-Bishop

of Osnabrück split up his diocese into 13 diaconates. By this time

the area had come under the civil control of the Count-Bishops of Münster.

It just so happened that a vigorous re-catholization campaign had created

a nominal catholic population which thus became frozen with the Treaty

of Münster and Osnabrück of 1648 (Treaty of Westphalia) which

advised via 'cuius regio eius religio' to the status of 1624 as the permanent

religious faith of an area. Actually it took until 1682 when the last bunch

of recalcitrant priests was fired to complete the Roman Catholic reconversion

of the Oldenburger Münsterland.

The Münster Count-Bishop Christoph Bernard von Galen started to

make waves about getting the spiritual side of his territory to match the

civil administration part of his principality in the mid 1660s. In 1667

he was able to purchase the Ämter Vechta, Cloppenburg, Meppen and

Bevergern from Osnabrück. Pope Clemens IX approved the deal the next

year. Thus ended a 100 year battle for religious-civil control of the Hochstift

Osnabrück which from now on became known as the Niederstift Münster.

Not much changed until the advent of the French Revolution. The general

rearrangement of the balance of power in Germany came to the larger and

powerful states as Prussia started to make its influence known.

Prussia had already occupied the city of Münster in 1802. The

Reichsdeputationhauptschluß of 1803 in Regensburg sealed the fate

of the religious principalities in Germany. The eastern part of the Fürstentum

Münster, the Niederstift, was given to the Duke of Oldenburg and the

western part, the Amt Meppen, to the Duke of Arensberg. The people rejoiced

that they did not wind us as a part of Prussia. The last Count-Bishop of

Münster, Max Franz, had died in 1801 and the suspense as to his successor

was now over. The area has stayed in the Münster Diocese to this day

even though it is not physically connected to it and is surrounded by other

dioceses.

Source: www.genealogy.net

written by Fred Rump

Did the southerners "feel" like Oldenburger's or did such politics

even affect them?

In the early

days there was relatively little contact. As the railroads and streets

or highways were built the folks down south actually got to see some of

those heathen northerners. :-)

In the early

days there was relatively little contact. As the railroads and streets

or highways were built the folks down south actually got to see some of

those heathen northerners. :-)

The walls were quite high and did not really fall until the post WWII

period.

One must remember that rulers were simply imposed on people for as long

as they knew. It was how things were. The Oldenburg state tried hard to

accommodate but also fought tooth and nail with the RC Church to have a

separate catholic diocese where they would be in control. Münster

fought back with equal vigor already having lost temporal power and not

wishing to cede the spiritual side also.

The Vechta setup was an accomodation of both sides where local clerics

could be appointed to head the Church somewhat free of Münster interferance

or overlordship. Yet, this battle continued with each nomination of the

head of the 'bischöfliches Offizialat' in Vechta. Much of this difficulty

was about money.

The RC Church funded much and with the secularization of its property

there came a lapse as to who would pay for what with what resources. Since

the state took income, it now also had to fund things it wasn't used to

do. It was not until the Convention of Oliva (Danzig) provided for the

responsibility of the secular state to fund religious institutions that

some sense was made of the mess.

Many of the difficulties came in a period of state-church conflict and

were encouraged by the Kulturkampf which attempted to take ancient habits

from the Church and hand these over to the state.

That all this cost money was not so nice for the secularists of the

time. Still, it survives to this day in Germany where the Church depends

on the sate for funding.

All this was particularly difficult because Oldenburg had always considered

the Protestant church as its partner and basically could call the shots

as to what that church was to do. With the Roman Catholic Church, they

had to talk to Rome. That went against their nationalistic instincts and

pride of being supreme ruler. After all, how many legions did the pope

have? Somehow the Catholic Church came to be subservient to the ruling

state/protestant partnership and equal rights before the law had yet to

be determined or agreed upon.

By the early 1870s things started to improve with the ordination of

locals Theodore Niehaus (Barßel) and his successor Anton Stukenborg

(Stukenborg near Vechta).

As to the question of how the Southerners felt - I think they accepted

Oldenburg quite well as long as they could live their lives in peace and

without undue und unjust rulings from above. Actually in their every day

life little changed. They still paid taxes and still went to church just

as they always had.

Source: eMail at June 6. 1999 to email-list oldenburg-l@genealogy.net

from

Fred Rump

26 Warren St. Beverly, NJ 08010 or

4788 Corian Court, Naples, FL 34114

(Please send comments to FredRump@earthlink.net)

Today:

See Oldenburg

and Niedersachsen.

See also the historical Fürstbistum

Osnabrück and Munster.

History:

History:

In the early

days there was relatively little contact. As the railroads and streets

or highways were built the folks down south actually got to see some of

those heathen northerners. :-)

In the early

days there was relatively little contact. As the railroads and streets

or highways were built the folks down south actually got to see some of

those heathen northerners. :-)